Is telling the trauma story necessary?

February 10, 2020 | Awareness, Trauma

Over the past three and a half years, I’ve supported and learned from people who have experienced sexualized violence. Many of them went through that and other forms of violence in their lives. I’ve seen the way that being hurt by other humans harms people. I’ve had the honour of accompanying them as they healed their wounds and learned to trust again. Doing this work has taught me so much about hope, connection, and love. It has also taught me about the nature of this work, and the ways in which therapy can impact a person’s journey to healing.

Two models for working with trauma

While working in this field, I’ve come across two overarching therapeutic models. One general approach seems to focus on teaching grounding techniques and then exposing the person to triggers, so that they learn to tolerate them. In this branch, there is often a period of retelling the narrative of trauma as a way of exposing the person to their memories and experiences. In my understanding, it’s all about reaching a point where the memories don’t cause dysregulation anymore; a place where the person doesn’t feel much (or anything) when the memories come back.

The other branch sees trauma as a having an impact on the body’s ability to interpret the environment and regulate itself. It typically involves techniques that help people get a handle on the intensity of what they were feeling, either because they were feeling too much or too little. Often, there is an aim to address any fractures on the person’s sense of self. In other words, this branch seems to seek the integration of all alienated parts, while helping the body remember how to better assess safety and connection.

There are approaches that exist somewhere on the spectrum between these two models. Some try to mix parts of the other. At the end, what really matters is that it works for the client. I was taught that the most important aspect of change is the fit between the therapist and the client. Fit, in turn, can be divided into three aspects: that the client and therapist like each other, that the client believes in what they’re doing with their therapist, and that the therapist believes in what they’re doing. It’s because of this last aspect that I can’t practice from the exposure and tolerance perspective. I believe that it’s an incomplete strategy at best and, at worst, it can be re-traumatizing for people.

Why I believe that telling me the story of your trauma is an unnecessary risk

I see trauma, in particular trauma inflicted by another human, as a short circuit to the nervous system. This shock often causes an injury to a person’s sense of safety and connection. Healing from this wound involves paying attention to the person as a whole, not only to the intensity of the inner experience when triggered. This means looking at the person at many levels and soothing, expanding, softening, and modifying chronic trauma responses. It’s this process that creates a new and integrated sense of self.

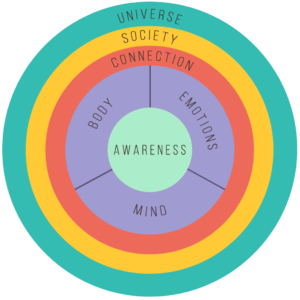

To better understand the person as a whole, I like to imagine that people have different parts with which they can form relationships. I visualize these sections in what I call the Plenitude Wheel. To summarize, I think of awareness as being at the centre of our ability to choose and change. By using it as a skill, we can monitor and manage the other parts of the self. This, in turn, helps us both explore and gently move what is there.

In terms of trauma, injuries and fractures can happen in one or more of these parts. In my practice, I always start by checking what part of the person is expressing the most distress, and finding ways to help the client learn to regulate or soothe that response.

Safety is kind of a big deal

Another big aspect in my work is the aim for safety. In my understanding of how the nervous system works, there is a threshold that, when crossed, turns off the higher layers of the brain. Namely, the cortex and parts of the limbic system. When this happens, people stop being able to make conscious choices or process their experience. They can only respond automatically, based on survival mechanisms encoded long-ago in our DNA. In other words, choice gets taken away. Fragmentation can happen again, as things occur without the involvement of the whole brain. For this reason, safety should be a priority. I believe we need to have access to our whole self, i.e. our whole brain, to create long-lasting change. To me, that is true healing.

So, is the narrative important?

A possible source of unsafety is the imagined. Because the brain doesn’t really know the difference between what is real and what is imagined, I tell my clients that we will wait to determine if the narrative is an important part of their healing process. If that is where we start, there is a chance that telling me the story (which is imagined and re-experienced in that process) could re-traumatize the client and take them to dysregulation. It could even reinforce the connections between the trigger and the trauma response, if the client doesn’t have the ability to moderate the latter.

This is the reason why I would set many boundaries if someone came to me wanting to tell me their story. I would want to know we have a strong relationship, and that we both feel comfortable and secure in their regulation strategies. Then we’d integrate that into the therapeutic process: Did it help? How does that change their experience? In other words, if we got to a point where telling me the story was important, it would be only one part of the process. It would have to be integrated like every other step.

Although the work does include expanding the window of tolerance, integration (healing the fractures) goes beyond exposure. The narrative is only one part of the person, and one where there may or may not be fractures. It’s about re-learning responses so that they’re more appropriate to the events in their life; it’s about seeing their life as a unified whole. In my experience, many people can get to this place without telling me more than a few discrete memories, sometimes without ever telling me anything. In my 3.5 years working with people who have experienced trauma, I have yet to work with someone who had to tell me their story to feel they have healed. To me, the possible gains don’t seem to outweigh the possible costs. I simply would rather not take the risk.

About this post

This post was written as a part of the first Therapeer Event hosted at justinlmft.com. The topic was, “is telling the trauma story necessary for treatment?” I’ve asked myself this question many times in the past. I was very excited to come across this event on Instagram; it gave me the push to write my thoughts on this matter. Read what I have to say below, and visit the link for more related content. Thanks for coordinating, Justin!

I grew up speaking Spanish. English is my second language. When I communicate in English, I make mistakes. I've chosen to let the writing on my blog reflect the kind of mistakes I make when speaking, so that you have an idea of what it might feel like to talk to me. I trust the message is still clear but, if it's not, please don't hesitate to ask me for clarification.

The information provided on my blog is a mix of my personal thoughts, professional approach, and articles related to mental health. The purpose of sharing all of this is to communicate the models at the core of my practice, as well as to provide education. I hope this will help to minimize some of the power imbalances related to my profession. The articles on this blog should not be considered as professional advice for any one person or group of people. If you have any questions about the appropriateness of this content for you, please contact a qualified mental health professional.